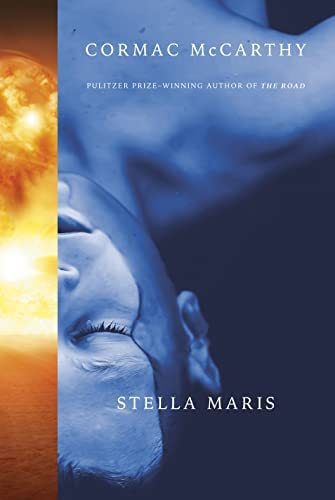

Cormac McCarthy

Stella Maris

An epic of worldly agony written solely in dialogue form.

"The more naive your life the more frightening your dreams (...) imperilment is bottomless. As long as you are breathing you can always be more scared".

"The world has created no living thing that it does not intend to destroy".

In the advanced age of 89 and after a 16-year period of literary apraxia, Cormac McCarthy, known as "the great pessimist of American literature", rebounds with the double-act publication of his two latest novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris, only a month and a half-apart and delivering his most controversial and commanding work in a career that spans over 5 decades. The elderly American author of monumental, however cruel and alienating in their mood and style, stories that marked the American literary canon of the twentieth century is at the time being working as a trustee in the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), a research center dedicated to the study of complex adaptive systems, and spends his time discussing with prominent scientists about a versatile set of subjects including technological, physical, and social disciplines. McCarthy has nonchalantly declared that he prefers the company of scientists to that of other authors and since 2014, his participation at the think tank located in New Mexico has led to him writing his first ever nonfiction work, an essay under the title The Kekulé Problem, in which he explores the intricate mechanics of the subconscious mind in relation to the human language and its use. The American author of 12 novels, 2 plays, and 5 screenplays claims that language is nothing more than a mere human invention and not a biologically determined phenomenon. What makes this dissertation a must-read is the fact that it is written by a man with no scientific background but with the fervor of the aficionado, the restless mind that never ceases to seek and extend his knowledge regardless of factors such as aging.

McCarthy is a much-revered fiction author in the U.S. and in 2003, the prolific literary critic Harold Bloom named him as one of the four great living American novelists sharing the courtesy title with the behemoth writers Don DeLillo, Philip Roth, and Thomas Pynchon. Blood Meridian is consensually deemed McCarthy's magnum opus, a novel published in 1985 -the authors fifth book in chronological order- and is today considered by many as the American Great Novel (GAN), a term which describes a canonical work of fiction scrutinizing, in terms of main themes, American reality in diverse historical periods, aiming to reveal the true nature and character of the country. McCarthy's novels have been mostly labelled Westerns and belonging to the post-apocalyptic genre, though what attracted the readership's attention to his work was his singular prose and the unconcealed nihilism suffusing the totality of his oeuvre. The disdain toward the use of punctuation earned him a notorious reputation among his peers and in his books, one cannot help but immediately notice the absence of any kind of marking on the page, whether it is commas, which he most often replaces with the coordinating conjunction "and", or quotation marks for dialogue, an artifice frequently used by authors who wish to impede the rhythm of their prose. It is a treacherous pick for writers as it can easily lead to the reader's confusion regarding who is speaking at any given moment in the text. The minimal use of So, I was wary when I started reading Stella Maris, a book that is based exclusively on dialogue, more specifically on the transcripts between Alicia and a member of the medical staff, Dr. Cohen, completely lacking any action and descriptive parts.

However, now I can sincerely say that the lack of punctuation marks didn't distract or frustrate me, and after the first few pages of the opening chapter, I felt like cruising along with the protagonist, Alicia Western, a unique female character, a disturbed mind who got lost in a labyrinth of its own making, a brilliant intellect paying the price of awareness -infinite despair- and, above everything else, a young woman staring at the abyss of a callous, godless universe that seems to be mocking and never allowing her to become a part of this world. It should be mentioned that McCarthy has an aversion to writing female characters and women in his novels have been rendered as whimsical and capricious creatures. Adam Rivett, in his review of the book published on The Sydney's Morning Herald's website (you can find it here), writes regarding the author's treatment of the female sex within his fiction: "Women have tended to occupy mythic forms: mothers and whores, echoes and archetypes". McCarthy himself, has stated in Wall Street Journal in 2009: "I was planning on writing about a woman for 50 years (...) I will never be competent to do so, but at some point you have to try". So, the time is now, almost 55 years after the last time that he wrote about a woman as a protagonist in his second novel, Outer Dark (1968), where the featured story is about a woman named Rinthy who is pregnant with her brother's baby, an explicit incestuous aspect implanted in the plot, something that the author is tempted to use again in Stella Maris, though in a more camouflaged manner and communicated to the reader through the employment of suggestive dialogue, with the protagonist speaking with innuendos and hurling tacit remarks to her psychotherapist who remains passive as a brick wall throughout the course of the book.

Alicia Western (it's up to you to decide if the selection of the protagonist's surname was made at random), a 20-year-old woman admits herself for the third time to a mental health care facility in Black River Falls, Wisconsin. The year is 1972 and Alicia has a long history of mental illness with her current diagnosis being paranoid schizophrenia, a labelling which she vehemently rebuffs as well as the other such as any other medical assessment ascribed to her. Her brother Bobby, whose story we followed in the previous novel, The Passenger, is half a world away in Europe in a comatose state after a nasty racing accident, a source of tremendous grief for his sister. The exact nature of the relationship between the siblings comprises one of the key-mysteries of Stella Maris, an account of the interchanges between doctor and patient which are loaded with hallucinations, weird dreams, melancholy, and references to the work and sayings of renowned scientists and philosophers. The interaction, though supposed to be palliative for Alicia's psyche, fell more like a monologue of the 20-year-old ex-prodigy child and mathematician who have excelled in the field of topos theory, or topology, at the University of Chicago while she has also made a stint in the equally mind-boggling game theory. Alicia's brilliance is no match for her therapist's wits and even from the first chapter I felt that she is the only one essentially speaking while with some scattered interruptions offering nothing substantial to the discussion. As A. Rivett puts it: "She's a wheel that can't stop turning, lost in the gears of forceful cognition".

This book precedes chronologically the previous one which begins with Alicia being found dead 10 years later in a case of suicide. In Stella Maris the author's voice, as the narrator of the story, is muted and in its place comes Alicia whose words weave a narrative of its own, a portrait of a woman who for as long as she can remember felt at odds with the world, never quite succeeding in belonging. Readers who are familiar with McCarthy's body of work will sense the distinctive quality of this book mainly from what is absent. The author's voice is replaced by the protagonist's: "What remain are human voices which is to say characters contending with one another and with their own fears and regrets, as they face prospect of the godless void that awaits them". Alicia's cadence feels recognizable and I think that McCarthy turned his attention to the classics and more specifically to the great William Shakespeare and let him inspire his fictional concoction. There is a Hamlet-like quality to Alicia who is obsessively preoccupied with the meaning, or absence of meaning, of surviving. The language that she uses is simple, further underlining the content which is dense, to say the least, and crammed with information so it would be best if you read this one with an open notebook and a pen in hand. In his "Guardian" review, Beejay Silcox writes that "Alicia is less a character, than a receptacle, a dumping ground for eight decades of snarled (and snarling) ideas" (read the full review here). Thus, the observant reader will discern how much of the author has been transplanted to the character and will obtain an idea of what he's obsessed with as he reaches the end.

The stichomythia between Dr. Cohen and his distinguished patient changes in respect to tone as we dive deeper in the consecutive dialogues, so the combination of erudite speech with reluctant suspicion which Alicia exhibits in the first part is replaced by a more confessional timbre, with Alice becoming more willing to talk about what really concerns her. There is a lot of talking about her hallucinations, a hallmark of schizophrenia, and the apparitions that keep her company with Alicia even giving names to them: there is the leading figure, "Thalidomede Kid" (or the "Kid") who is a kind of spokesperson or representatives for the rest of the chimeras that torment Alicia since her early teens. The psychotic symptoms that Alicia deals with are further burdening her feelings of detachment from the "real" world, making her melancholic and yearning for something to hold on to. We read: "at the core of the world of the deranged is the realization that there is another world and they are not a part of it". This short phrase epitomizes the essence of what is described today as "mental illness". At another point, she says to Dr. Cohen: "If I had a child, I wouldn't care about reality". Motherhood, in Alicia's head is the ticket to existential oblivion while her scientific interest in mathematics seems to have dwindled despite her impressive achievements. Her "divorce" with the thing that she used to love more than anything in life was traumatic as she acknowledges: "I think maybe it's harder to lose just one thing than to lose everything".

With the danger of sounding macabre, perhaps this is McCarthy's valedictory work and I think that it's definitely his most aspiring project, brimming with hidden meanings expressed through innuendos and things left unsaid, touching many themes -some of them with an academic hue- and allowing the reader to enter into the disturbed, however radiant, mind of Alice. McCarthy has won the bet and proves that he is absolutely capable to create women characters, even if the oddities of Alicia deem her gender an almost irrelevant issue. Keep in mind that this is not a sequel to The Passenger, nor a book that can be read in parallel. Many have more effectively described as an appendix to #1. Of course, both books share, more or less, similar thematics but the differences in style are convincing enough to set them apart. It is important that you read The Passenger first even if its story precedes chronologically this one, however as you will understand when you finish reading, there is a good reason for that.

About

The Passenger #2