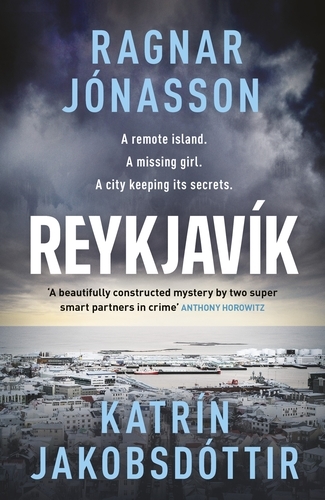

Ragnar Jónasson/Katrín Jakobsdottír

Reykjavik

Of historical relevance, though weak as a crime story.

One of the most keenly anticipated crime novels of 2023, Reykjavík is the result of the fruitful collaboration between the well-esteemed author Ragnar Jonasson and the woman who currently serves as the country's Prime Minister, Katrín Jakobsdóttir. While there are internationally a few examples of prominent politicians who resolved to write a crime novel, such as Winston Churchill, who wrote a thriller under the title Savrola during the 1920s, Jimmy Carter, Bill and Hillary Clinton or a name closer to the Nordic reality, Anne Holt, who has served as Norway's Minister for Justice in 1996 and 1997, it is the first time ever that an active head of government puts their name on the cover of such a book. Jakobsdóttir holds a degree in Icelandic literature and her master thesis was on the work of Iceland's godfather of noir prose, Arnaldur Indridason, thus her involvement in this project was far from incidental. Reykjavík is a simply written, straightforward cold-case procedural spanning three decades in terms of timeline (1956-1986) and featuring more than one protagonist. The plot relies heavily on the whodunit element and the finale was a surprise for me as I guessed wrong in respect to the culprit's identity.

The novel lacks excitement and is reminiscent of Jonasson's less successful standalones, however earns some critical points due to the authors sprinkling the text with snippets of information regarding Iceland's social and political status quo during the 1980s, the decade which was marked as the end of the Cold War. We learn about the airing of the firs private TV channel in Iceland, Reykjavík's developmental booming which gave the city the shape and size that we know today, while there is a special mention of the 1986 "Reykjavík Summit" between the President of the United States, Ronald Reagan, and the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, which was held on 11–12 October 1986 and took place in the former French consulate, a house called Höfði. The meeting signals the story's climax, and the solution to the mystery is given through the media frenzy and the authorities' restriction measures. Even though the historical facts are more than welcome, the authors don't dwell on details and, most importantly, they fail to integrate those morsels of information within a wider, meaningful context that could offer authentic insights to the reader. Thus, they are constrained to being the background for the story's -feeble- action.

The story commences in 1956 with a young police officer, Kristján Kristjánsson, travelling to the little island of Videy, off the coast of Reykjavík, in order to investigate the mysterious disappearance of a teenage girl, Lara Marteinsdóttir. Lara used to work there as a maid for a big shot barrister and his blue-blooded wife. Kristján immediately senses that something is amiss as the couple's answers are evasive and suggest that, perhaps, they had been involved in the case. Nevertheless, the top brass is eager not to rock the boat and bother VIP citizens with police interrogations, and Kristján is not free to pursue the sporadic leads to get closer to the truth. The case is shelved and years are passing by. Throughout the first third of the novel, the authors move forward by a decade each time, conveying the -now aging- detective's disappointment over a case that was in the national spotlight for ages. When we finally reach 1986, the present or "now" of the narrative, we are introduced to a young tabloid journalist, Valur, who digs up Lara's case in order to write a series of features for his newspaper. However, when he takes a call from an unknown woman who has a hot tip, Valur realizes that maybe he will have the opportunity to shed light on a case that perplexed the police for several decades.

I won't write anything more about the plot as it would be nothing but spoiling the novel, which has its merits while, sadly, lacking that unspecified factor that would make it stand out from the generic works of Nordic crime fiction. Although I am a huge fan of the austere, frugal prose, I found the language to be overly simplistic and perhaps there is something off-center as far as the English translation is concerned. I thought that there were some essential pieces of text left out, but perhaps this is only my imagination. Overall, Reykjavík is a novel that will appeal to the fans of Scandinavian crime fiction, but its reach ends there. Wider readership demands something more in order to take a leap and try the gloomy settings and plot machinations of the Nordic noir genre.