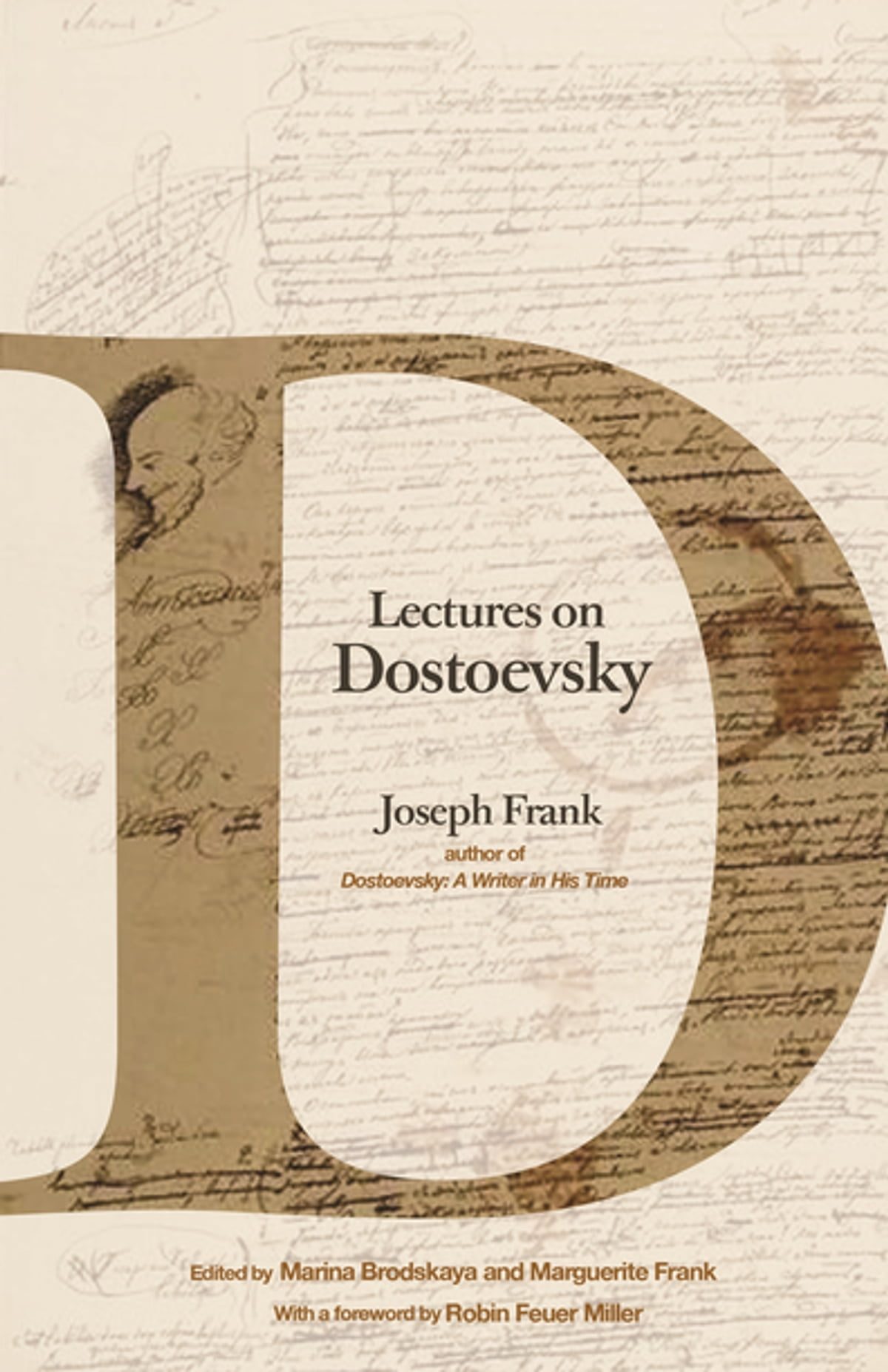

Joseph Frank

Lectures on Dostoevsky

An educated take on Dostoevsky's most significant works by Joseph Frank.

Joseph Frank was an American professor of comparative literature at the Universities of Stanford and Princeton and his name is inextricably linked with the painstaking study of one of the most influential writers of the 19th century, Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. Frank's five-volume biography on the Russian literary giant, an iconic work that exceeds the 2500 pages, deem him the aptest person to analyze Dostoevsky's body of work and these never-before-published collection of Stanford lectures examine one-by-one the most significant novels that marked modern literature and earned the author a place among the greatest European philosophers and intellectuals of the two previous centuries. Dostoyevsky's novels are explored through the lens of the socio-political reality in Russia at the time as well as the peculiar idiosyncrasy of the writer himself that is often projected to some of his most well-known characters. Frank's penetrative gaze leaves no question unresolved and this compilation proves to be an invaluable companion to Dostoevsky's most significant writings.

After a brief introduction in which Frank clarifies that the main target of the lectures is to "introduce the main literary and ideological elements" of Dostoevsky's work, the American academic presents an in-depth analysis of seven novels: Poor Folk, The Double, The House of the Dead, Notes from Underground, Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamazov. It came as a surprise to me to realize that Frank chose to left out one of the most profound and emotionally charged Dostoevskyan works, that is Demons, even though the book is mentioned in several other parts of the lectures. There is a clear distinction between the Russian author's early work that includes the first four titles and his mature period that begins with the publication of his masterpiece, Crime and Punishment in 1866. In order to better grasp the nuances between the two phases, Frank provides information on Dostoevsky's first years of life as an educated youngster who, defying his father's wish to become an army engineer, consciously chose to become a writer.

He also points out that Dostoevsky's life as an author differentiated from that of his Russian contemporaries in the sense that for him, writing was the only source of income, thus he strived to create stories that, apart from endorsing universal themes, also contained elements of mystery and suspense that made them more alluring to the masses. In his article "Feodor's Guide: Joseph Frank's Dostoevsky", David Foster Wallace writes that Dostoevsky's novels "almost always have just ripping good plots, lurid and involved and thoroughly dramatic. There are murders and attempted murders and police and dysfunctional family feuding and spies and tough guys and beautiful fallen women and unctuous con men and inheritances and silky villains and scheming and whores". A prime example is Crime and Punishment, a novel that could readily be considered a crime novel in today's standards as it bears all the hallmarks of the genre. Of course, there is so much more in this novel than a simple story about murder and literary critics and scholars have devoted plenty of ink, tracing and debating the main themes and closely examining the main characters.

One of Frank's main arguments is that it is impossible to get a profound insight into Dostoevsky's work without scrupulously investigating the social and cultural milieu in Russia during the time in which the author created his major novels. Foster Wallace writes that "Frank persuades us that Dostoevsky's nature works were fundamentally ideological novels and simply cannot be read unless one understands the polemical agendas that inform them and to which they were directed". During the 19th century, a new group of young, educated people with radical ideas who opposed the existing status quo as established by the previous generations, the so-called "intelligentsia" challenged the traditional foundations of Russian political and religious reality and gained power within the upper class. At the same time another schism was brewing between the "Westernizers", those who believed that Russia should adopt the European ways in politics and culture, and the "Slavophils", the majority of simple Russian people, often illiterate, who insisted that their country's unique set of characteristics should be preserved at any cost. Even though, Dostoyevsky was heavily influenced by the work of European authors such as Balzac and Hugo, he remained a reluctant Slavophil, mainly because of the issue of religion.

These clashes in the inside of Russian society gave rise to the Russian Nihilist Movement, a school of thought that incorporated aspects from different philosophies such as materialism, positivism, atheism, and most importantly rational egoism. Even as a youngster moving within the circles of the intelligentsia, Dostoyevsky remained skeptical about the potential of Nihilism and doubted its principal doctrines. One of the main reasons for his stance was his unwavering belief in the Christian God who, according to Dostoevsky, represented the only hope for salvation. Rational egoism was rejected as the exact opposite of salvation for the society as it was an ideology that eradicated human sentiments such as love and compassion, the backbone of any healthy human relationship according to Dostoevsky. His distrust in the ideal of Nihilism is evident in his novels, the most prominent example being again Crime and Punishment where the protagonist, Rodion Raskolnikov, is a young nihilist who decides to move a step beyond theory and proceed to action. Dostoevsky wanted to show what happens when an anti-human ideology is put into action and Raskolnikov's decision to kill the elderly pawnbroker, an act that he views as beneficial for the society as a whole, leads to the inevitable feelings of guilt that torment him throughout the course of the novel. Raskolnikov is the archetypal tragic hero who loses his grip when he acts on the basis of his false ideas. The murder of the pawnbroker is the ultimate nihilistic act, but instead of providing satisfaction to the doer, it destructs his innermost self.

Dostoevsky was a man who lived a hard life, filled with loss and suffering, while his passions brought him on the brink of disaster in many occasions. His compulsive gambling was the main reason for which he was almost constantly broke and desperately begging for some rubles from friends and acquaintances. In Sigmund Freud's article "Dostoevsky and Parricide", the Austrian psychoanalyst sees a connection between the Russian author's personality traits and the -alleged- murder of his father by his serfs in Moscow when Fyodor was a young man. He further proceeds to link Dostoyevsky's epilepsy, that plagued him throughout the course of his life, with the aforementioned event and seems to believe that his condition was just a symptom of a more generalized, serious form of hysteria. Frank quickly dismisses Freud's claims and remains loyal to his study of the context within which Dostoevsky conceived and imprinted his stories as the most crucial aspect of his study.

The breakthrough in Dostoevsky career coincided with the publication of his first novel Poor Folk in 1846. The book was an instant critical success and Dostoevsky was hailed as one of the most promising writers of his time. The publication of this novel was the event that made Dostoevsky become acquainted with one of the most prominent Russian literary critics, Vissarion Belinsky. Belinsky welcomed Fyodor to his circle of friends and his enthusiastic reviews for Poor Folk contributed in the warm reception of the book by the country's readership. Later, Belinsky and Dostoevsky had a fallout due to Belinsky's embracement of atheism, under the influence of Feuerbach's views on God and religion, and their roads never intersected again. In his first fully-fleshed novel, Dostoyevsky adopted the epistolary form, a narrative technique already employed by numerous Western authors, and as a result the characters were endowed with human dignity, even though they belonged in the bottom scale of the social hierarchy. Frank writes: "Dostoevsky was implicitly saying that even a clerk on the very lowest level and a young girl who came from a very poor background (...) have the same refined feelings and sensitivities as those originating from a much higher social level".

Frank's perspective on each one of Dostoevsky's novels is shrewd and the reader who is familiar with the stories will find a fascinating aide to some of the most acclaimed, classic works of Russian literature. In this review, I opted not to write an analysis for each one of the lectures, as it would be boring, and I preferred to mention some general information regarding Frank's perception of Dostoevsky's work interspersed with selected biographical facts about the author himself that will prove to be helpful in navigating through the totality of the seven chapters. Of course, one could write and write endlessly about an author of this caliber and his captivating texts that remain topical even today in spite of being written nearly two centuries ago. Joseph Frank fully justifies his reputation as the most extrusive Dostoevsky expert and reading this book motivated me to try my luck with the enormous biography that remains a point of reference for every Russian literary scholar around the world.